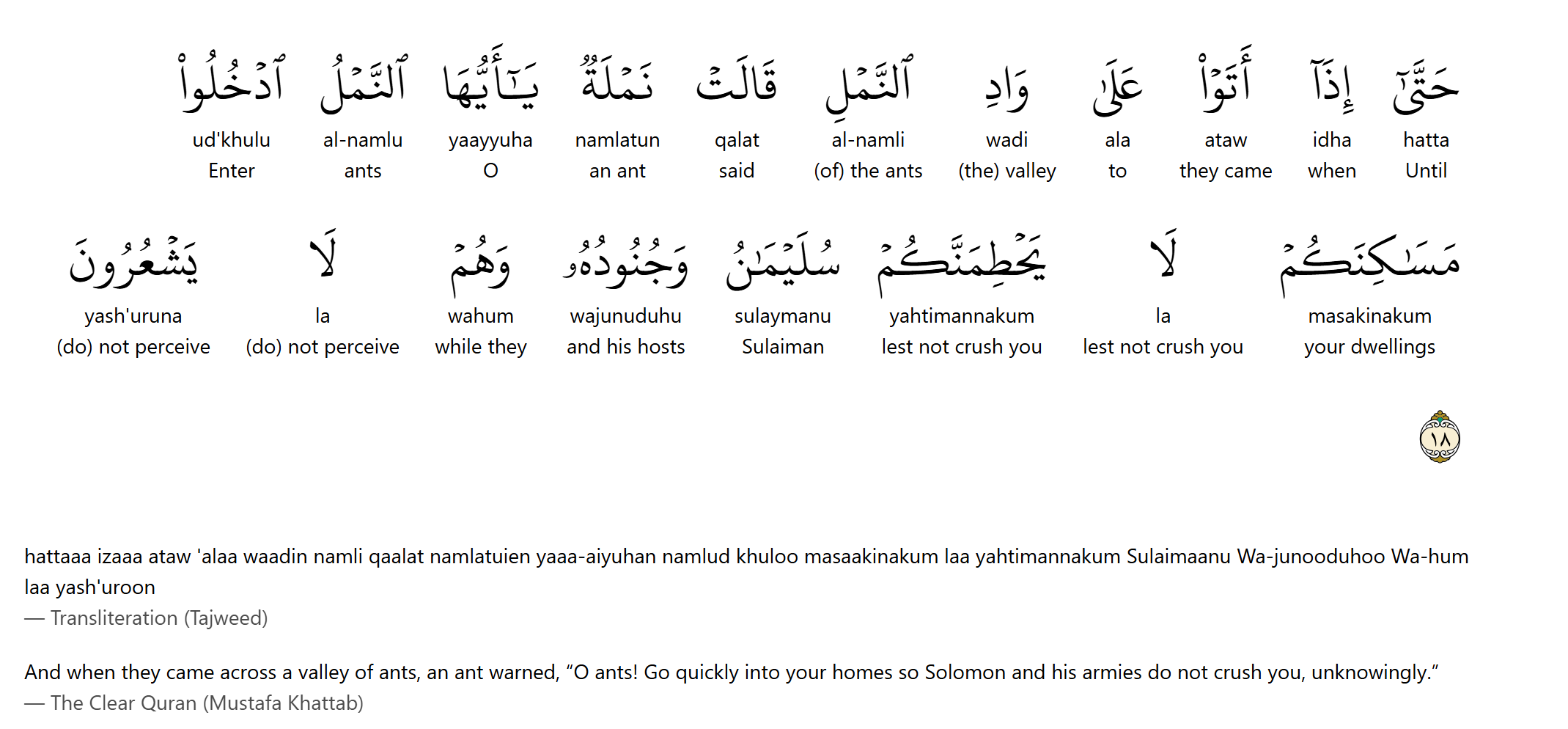

SURAH AN NAML: AYAT 18 (QURAN 27:18)

Ants are among nature’s most astonishing architects of cooperation, forming colonies that function as unified, intelligent systems. These colonies, often hidden beneath soil or nestled in tree trunks, are not merely nests—they are dynamic hubs of activity, communication, and purpose. Each ant, though individually simple, contributes to a collective intelligence that enables the colony to forage, defend, and reproduce with remarkable efficiency. Their ability to coordinate without centralized control has inspired fields as diverse as swarm robotics and optimization algorithms, demonstrating how biological systems can solve complex problems through decentralized logic. Within these subterranean cities, ants communicate through pheromones, touch, and even sound, creating a living network that rivals engineered systems in elegance and adaptability. The structure and organization of an ant colony reveal a profound lesson: that unity, even among the smallest beings, can yield extraordinary power.

Ant colonies are marvels of biological organization, functioning as superorganisms composed of thousands—sometimes millions—of individuals working in harmony. At the heart of this system lies a sophisticated communication network that enables ants to coordinate complex tasks with remarkable precision. Their primary mode of interaction is through pheromones, chemical signals that convey everything from danger alerts to food locations. When a forager discovers sustenance, it lays down a pheromone trail on its return, guiding others to the source. These trails intensify with repeated use, functioning like a dynamic GPS system. In addition to chemical cues, ants also employ tactile communication—antennae touches that transmit nuanced information—and, in some species, acoustic signals produced by stridulation, a rubbing of body parts that resonates in the dark confines of their nests.

The social structure within an ant colony is equally intricate, with a clear division of labor based on caste and age. The queen serves as the reproductive nucleus, laying thousands of eggs to sustain the colony’s population. Male ants, or drones, exist solely for mating and perish shortly after fulfilling their role. The bulk of the colony’s workforce consists of female worker ants, whose duties evolve over time. Young workers typically remain within the nest, tending to larvae and maintaining infrastructure. As they age, they transition to more hazardous roles like foraging and defense. This dynamic labor allocation ensures that each ant contributes optimally to the colony’s survival, adapting fluidly to environmental demands.

What makes ant colonies truly extraordinary is their ability to self-organize without centralized control. Through decentralized decision-making and responsive communication, ants exhibit a form of collective intelligence that rivals engineered systems. Their ability to reassign roles, reroute foraging paths, and respond to threats in real time has inspired innovations in robotics and network theory. These tiny architects of order demonstrate that even the smallest creatures can embody profound lessons in cooperation, adaptability, and resilience.

In Surah An-Naml (27:18), the Qur’an recounts a moment when Prophet Solomon hears an ant warn its colony: “O ants! Enter your dwellings, lest Solomon and his hosts crush you while they perceive not.” This verse, revealed over 1,400 years ago, describes a level of ant communication that modern science has only recently begun to understand. Ants are known to communicate through pheromones, tactile signals, and even acoustic vibrations—methods that allow them to coordinate complex behaviors like foraging, defense, and nest maintenance. The Qur’anic depiction of an ant issuing a warning aligns strikingly with what entomologists now recognize as alarm signaling within ant colonies, a phenomenon that involves rapid dissemination of danger cues to protect the group.

What makes this verse particularly miraculous is its scientific accuracy despite the absence of any technological means to observe such behavior at the time of revelation. Recent studies have shown that ants possess sensory hairs on their legs capable of detecting ultrasonic vibrations, allowing them to perceive approaching threats. Furthermore, ants can produce sounds by rubbing specialized abdominal structures, a form of stridulation that serves as a rudimentary language. The Qur’an’s reference to an ant speaking/communicating and warning its peers not only anticipates these discoveries but also underscores the depth of divine knowledge embedded in its verses. This convergence of scripture and science is a powerful affirmation of the Qur’an’s divine nature – revealing truths that transcend the boundaries of time and human understanding.