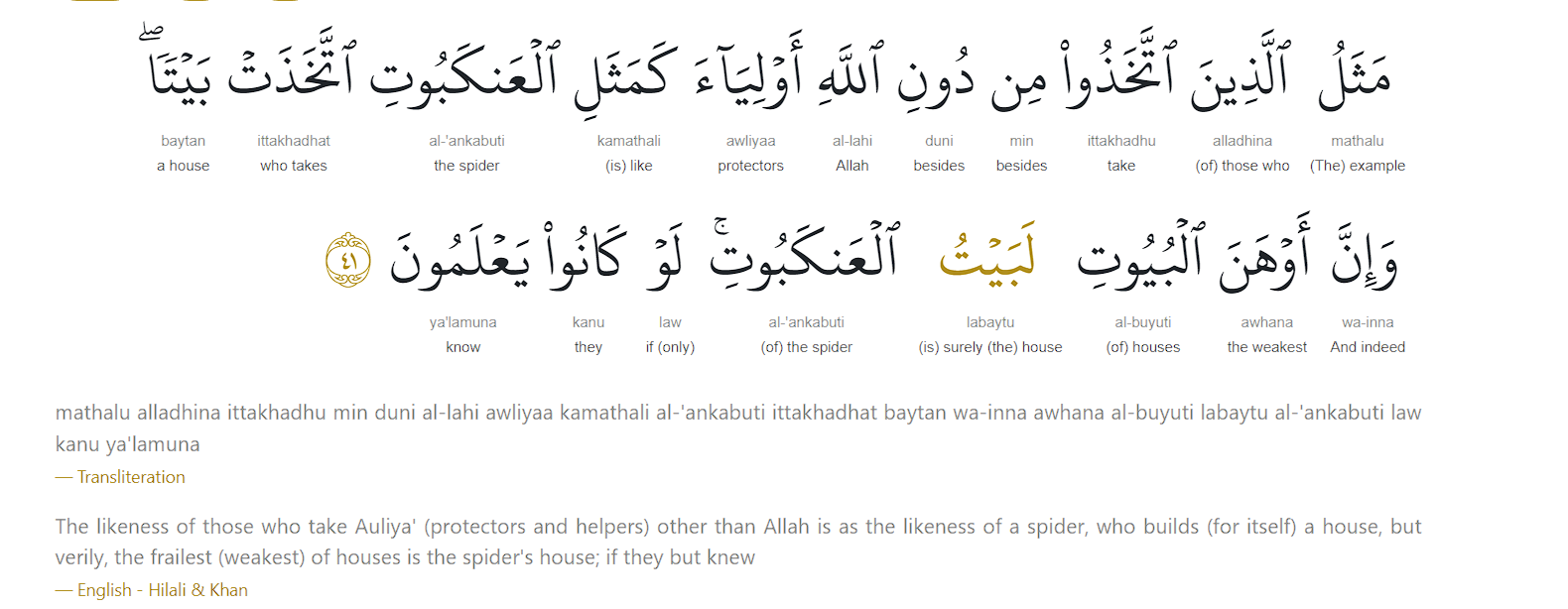

AL ANKABOOT (THE SPIDER): AYAT 41 (QURAN 29:41)

Spiders are known for several defining characteristics — their numerous legs , numerous eyes, and of course their ability to create intricate webs. Spider webs have existed for at least 100 million years, as witnessed in a rare find of Early Cretaceous amber from Sussex, in southern England. What has not been known until recently through arachnological literature – is the fact that it is predominantly the female spider that generates the intricate webs we know so well.

This is due to several factors. Female spiders tend to be a lot larger than male spiders due to their obligation to birth as many babies as possible. This large size gives them the required energy and physical ability to construct relatively large webs. Additionally, many female spiders use their large web to catch/store prey that they can share with their spiderlings and, in some cases, their male counterpart.

Males generally do not create webs. If a male spider does create a web – they generate smaller webs because of their (typically) smaller size and because they don’t have the time to create something so impressive. Male spiders have the primary objective of finding and mating with a female, and they spend a significant amount of time trying to do just that. Therefore, they’re not often in one place for long enough to create a large web, or they simply don’t have the ability to make one.

In Surah Ankabut: Ayat 41 (29:41) – Allah mentions the web of a spider. “It-takhatha اتَّخَذَ” is for males. “It-takhathat اتَّخَذَتْ” is for females. The Quran used “It-takhathat” for females – Here the female spider builds the web. Amazing information from something revealed approximately 1400 years ago in the Arabian peninsula (a society typically with male dominant households).

Also – In the intricate world of arachnids, the spider’s web—often admired for its architectural finesse—conceals a social structure marked by profound isolation and brutal sacrifice – with the Quran emphasizing it being the “weakest” of houses . Unlike eusocial insects such as ants or bees, spiders are largely solitary, and when they do interact, the encounters are often fatal. In many species, the female spider exhibits sexual cannibalism, consuming the male either before, during, or after mating. This behavior, observed in species like the Australian redback spider, is not merely incidental but may serve evolutionary purposes: males that sacrifice themselves can increase their reproductive success by ensuring more of their sperm fertilize the female’s eggs.

Yet the cycle of sacrifice does not end with the male. In a phenomenon known as matriphagy, certain spiderlings consume their own mother to survive. Species such as Stegodyphus dumicola, native to South Africa, demonstrate this chilling behavior. After hatching, the young are fed a nutrient-rich fluid regurgitated by the mother, a process that gradually liquefies her internal organs. Eventually, the offspring swarm her and begin to eat her alive—a grim but efficient strategy to ensure their survival in harsh environments. This behavior has been documented in studies like those featured by National Geographic and Roaring Earth, underscoring the extreme cost of maternal investment in some spider societies.

Taken together, these behaviors reveal a social framework that is not only fragile but fundamentally antagonistic. The spider’s home, while structurally resilient, is socially tenuous—built on a foundation of consumption and sacrifice rather than cooperation. The absence of enduring bonds, communal care, or reciprocal relationships renders the spider’s domestic sphere one of the weakest among social animals. In contrast to the nurturing dens of mammals or the bustling hives of insects, the spider’s web is a stage for solitary survival, where intimacy often ends in death.